Warning: This article discusses death and includes images of deceased people and includes links to photos that may be distressing to some people.

Death and Dying in Torajan culture has not changed from its centuries-old traditions, even though more than 85% (out of a population of around 450,000), are Christian, the rest include Muslim, Hindi, and Buddhists.

For Torajans, death is not the end. It’s an extension of life.

Many follow Aluk To Dolo ( the way of the ancestors), in combination with their Christian or other religions.

Like some Central and South American Indians, they have integrated aspects of their rituals with Christianity.

For instance, Day of the Dead is one that is practiced in conjunction with Catholicism and other religions in South America.

On the day (23rd November from memory), the locals go to the cemetery to celebrate the life of the departed. They will sit on his grave, have a picnic, then leaving behind food for the departed who will eat it (supposedly), during the night after the relatives have gone home.

When they come back the next morning, if the food is gone, then the departed enjoyed the cooking.

If there is still food at the gravesite it means the departed didn’t like the dish, so they will try to give a better meal the following year.

It is unusual that any food is found the next morning, as the homeless secrete themselves around the cemeteries during the day to enjoy a feast once the relatives have gone.

So, who are Torajans, and where on earth do Torajans live?

The official name is Tana Toraja, and it is in the highland area of South Sulawesi in Indonesia.

After Bali, it is the place most visited by tourists in Indonesia but no one comes here for surfing and nightclubs.

They come here to witness one of the most macabre funeral rituals in the world.

The Traditional Rituals for Death and Dying in Torajan culture

The day-to-day, rituals of your average Torajan community are similar to any community almost anywhere in the world.

In a picturesque setting with unhindered mountain views and mostly clear skies, children go to school and adults go to work.

Basically, their lives vary little from those in the Western world. However, there is one aspect that sets the Torajan culture apart from others and that is, the way they handle death and dying.

Torajans are totally fine living with the dead.

In western culture “No one really talks about death.“ because it is sad. Western culture is slowly (very slowly), coming to grips with death.

Death doulas have been around for a few decades in western society, and some groups are pushing for greater recognition of death doulas.

For the Torajans becoming acquainted with death begins in childhood. For them, a dead person is treated as a sick person (Toma Kula), until it is time for the funeral, which can sometimes be years away.

Unlike deaths in western society, where the deceased is interred about a week after death, Tana Toraja funerals can only take place between June and October, the driest months of the year.

The reason is not necessarily the weather but, the cost.

Click here for a free e-book on Surviving final Goodbyes.

Origins of the Tana Toraja Funeral Ritual

It is thought these death rites originate from about the 9th century perhaps even earlier.

According to legend the elaborate death and funeral rites of Torajans originated when a hunter named Pong Rumasek entered the Bala mountain jungle and found a dead body in poor condition and without clothes.

Pong treated him well, put clothes on him, and buried him in his rightful place.

From then on Pong had better harvests, and when hunting he always returned with an animal to feed his family.

The interesting thing is, Pong always met the spirit of the corpse when working the fields or hunting. That is why Pong always told his children to care for and value the corpse, even if it was left without form.

This story has been passed down by the generations throughout the centuries.

Traditional Tana Toraja care of the deceased before the Funeral Ceremony.

After a person dies, Torajan culture does not consider the deceased dead.

They are considered to be Toma Kula (sick), however, the immediate family has a mourning period where the body is treated with a mix of formaldehyde and water, or injected with formaldehyde. Then using a mix of potpourri fragrances and burning sandalwood they mask the odour.

It takes about a week for the odour to subside, but they will still maintain a potpourri mix of fragrances to keep the home fresh.

In the past, the body was treated with a mix of sour vinegar and tea leaves.

The body is kept in the southern most room of the family Tongkonan, sometimes in a coffin, with the head facing west, because they are considered to be in a state of “transition”.

While they are still in the home, the Torajans believe the soul is still present, and they are bought food, water, and even cigarettes to keep them comfortable. This only happens if the person lived an honorable life.

A well-preserved body is regarded as good fortune and the family will do their best to keep the deceased well-preserved. Until the expensive funeral ceremony, known as Rambu Solo, is held.

The cost of the funeral is extreme even by western standards, and the time needed to get the money together can take years.

Officially, The longest nobles are permitted to store the deceased in the home is 36 nights. If they fail to have the funds by then, the body is moved to a cave in the hillside and left in a marked coffin.

Outside the nobility, it could be less than time than that, or the body was not kept in the home at all (because the ceremony was too short), or the body stays in the home for years.

The idea behind the 36 nights is that the sooner the body has a funeral ceremony, the more opportunities there will be for other blessings.

The Costs of Tana Torajans Funerals

Depending on a persons position in their society the costs can be eyewatering : anywhere from $50,000 to $500,000 in USD.

This, in a country where the average daily wage is about $6 US!

Having a ceremony is essential. Because it is their belief that it is only after this ceremony, which can last from 3 to 11 days, the soul begins its journey to Puya, the land of the spirits.

The biggest cost for the family is the cost of the sacrificial water buffalo(s). The families standing in society will determine how many buffalo they can afford for sacrifice.

Their belief is, that the more buffalo that are sacrificed, then the quicker the deceased’s soul will make the journey to Puya and the afterlife.

The values of buffalo vary and are determined by the color of its eyes, the markings on its skin, and the size of its horns.

Albino buffalo with light-colored eyes are the most valuable.

At livestock markets, a buffalo in good condition will sell for US$10,000 up to $40,000+.

The average middle-caste family would likely have eight to twelve buffalo for their ceremony, but it doesn’t stop there.

Relatives are also expected to provide a beast as well.

For the lower castes, pigs are also used to help speed the deceased’s journey to Puya although they should have at least one buffalo.

In keeping with the macabe party atmosphere, there will also be cock fights, and in keeping with the ceremony’s theme they will fighting to the death. Winners and losers will also form part of the menu.

To meet these costs Torajans work hard from an early age to accumulate money, mines in the area is one source that provides well-paid jobs.

Relatives working overseas will also be asked to contribute, actually, they will be expected to attend.

Click here for a free e-book on Surviving final Goodbyes.

Unlike western societies where a wedding is generally the most celebrated ceremony. Torajans don’t work towards their own benefit or to have the trappings of a western lifestyle, they save for the purchase of sacrificial buffalos.

Young men will delay a wedding if Grandma is in failing health, just so they are not burdened with more expenses or debt in the event she dies before the anticipated wedding.

If you are not able to pay cash for a buffalo you can secure it using your home as collateral. Losing a home is a very real possibility if the payments are not met.

Some young Torajans feel trapped by these traditions. Others have chosen to live and work in other countries (Australia for example), where they can enjoy a modern lifestyle, yet are not too far away from their home.

Pre-covid, a flight from say, Melbourne to Indonesia could be had for less than AU$1000.00 return, even less from other cities closer to Indonesia.

(Rambu Solo, The Great Goodbye) The Farewell Ceremony.

In the past Torajans buried their deceased with buffalo and pigs (animism), so the deceased would have something to offer the spirits on their way to the afterlife.

The ceremony begins in a respectful way with everyone dressed for the occasion. But after the buffalos are paraded, then led to the sacrificial site things become a little more chaotic, particularly at the lower caste ceremonies.

Particularly if a buffalo doesn’t want to be sacrificed! (warning: video of buffalo sacrifices)

The killing of the buffalo, pigs, and roosters is a noisy and gruesome affair. Adding to the noise are the vendors selling drinks, snacks, and cigarettes.

This is becoming more common as more tourists visit these ceremonies. As far as the Torajans are concerned the more “guests” in attendance the better.

Only when the first buffalo’s throat has been slashed, and it has bled to death is it acknowledged that the deceased person is “officially” dead, and their soul is on its way to Puya and the afterlife. The killing of other buffalos is said to speed the process to the afterlife along.

After the sacrificed animals are killed and their heads removed they are lined up side by side so the deceased can use them.

It is important that the blood of all animals touches the earth. Young boys are encouraged to collect blood squirting from the throats of buffalos in bamboo tubes as it is considered sacred.

The beasts are then butchered, and the ceremony continues with dancing and feasting for 3 or 4 days before the coffin containing the body is taken to its final resting place.

For some idea of the size of the ceremony, say 10 buffalo are sacrificed, their dressed weight might be around 450 kg each. So there is 4,500 kg of meat to be consumed in around a week.

If the family is from the nobility, there will be more buffalo sacrificed.

So, there is enough to be basically enough food to be feeding 7-8,000 people for more than a week!

Eventually, the heads of the animals will be returned to the Puya (place of the soul or spirit of the deceased), and the horns removed and placed on the home, and the more sets of horns there are on a house, the higher the status of that family.

The Final Resting Place and Memorials for Torajans

In reality, there is no such thing as “Rest in Peace” in Trojan society.

The “burial” doesn’t take place until all the “festivities” are completed, again it is dependent on the status of the family as to where their deceased relative will be “buried” (positioned might be a better term).

There are 4 options (generally).

- They find a cave to use as a burial chamber

- They carve a grave into large stones.

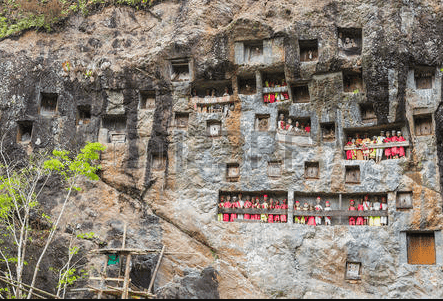

- They may use “sky burials” by hanging the coffins on the side of a cliff

- Store the bodies in a Patane, which is a smaller version of a traditional house.

Some burial caves are 100ft above ground level, meaning the higher the burial cave, the higher the status the family has.

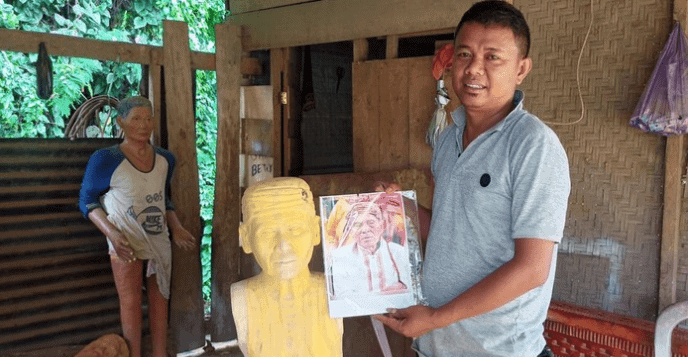

Although less of a practice now due to thieves stealing and selling them to tourists, a Tau Tau (a “portrait” of the deceased), is carved from wood or bamboo and placed on a balcony overlooking the valley below.

There are two kinds of statues:

- tau-tau nangka, which is made from the durable, gold-colored wood of the bread tree or jack fruit (nangka), and:

- tau-tau lampa, made from bamboo and cloth.

During the process, when the statue is ready, the Mebalun or the shaman kneels in front of it and turns it around to wake it up. Then he offers some pig meat and rice and a chute of rice wine. The family members give some sirih leave and tobacco and ask for its blessing and longevity. Later the women hug the tau-tau, press their face against the red face and express long complaints. After that, the statue is brought to the ritual field together with the body. After the funeral, the tau-tau is undressed. All that is left on the field is the green bamboo: the body has left to its ‘house without smoke’, the spirit has left for the south, to Puya and the relatives have gone home.

Indonesian Tourism.

In the higher caste areas, often a permanent wooden statue is carved besides the tau-tau lampa. These statues are commonplace in the cave areas. They are also seen as meeting places for the spirit; Their role is to guard the excavated grave tombs and to bless their descendants.

Children’s Funerals in Tana Toraja.

This ritual is equally bizarre. If a child dies before they have teethed, they are buried in a tree!

For babies who have not ‘teethed” the tree chosen is a Tarra tree. This tree produces a white sap that is considered a replacement for mother’s breast milk. The process is to cut a hollow into the trunk of the tree.

The baby is then wrapped in cloth and inserted into the hollow, then the hollow is closed up with strips of wood fastened to the tree trunk.

All other children follow a similar ceremony to the adults.

Resting in Peace is not easy for the Dead.

In western society we bury our dead and leave them in peace visiting every now and then to leave some flowers or say a prayer.

In Tana Toraja society, it is common for the deceased people to be attended to by their families after the funeral and burial.

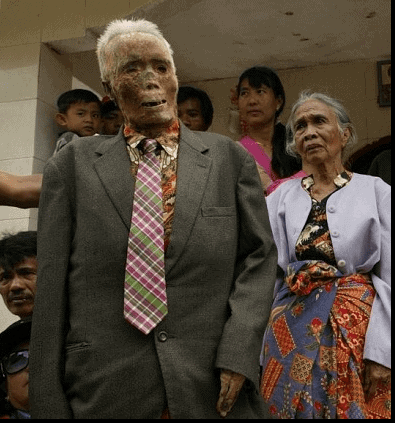

Pangala Village and Baruppu Village carry out a ritual called Ma’Nene every year.

Other villages may do it every three years.

In other place it can be done just by a family if they have relatives visiting.

In this ritual the preserved corpses are exhumed, groomed and dressed in new clothes, before being paraded through the village.

After the bodies are removed from their coffins, they are given a new set of clothes, hair (if any), combed. Men will probably have a cigarette placed between their teeth and lit by a grandson, other items they may have used while they were alive could be added as well, sunglasses, hats etc.

While the ritual itself may seem bizarre, the reason for it, is Torajan society keeps an unbroken relationship between families even though they are separated by death.

It is an opportunity for newer members of the family to meet their ancestors

The Darker side of these rituals and Comparision with Other Rituals.

Often the money to pay for them is borrowed, if they default on the loan then they will lose their home.

While the rituals in Tana Toraja are unique, a Patane would not be unusual to Catholics who build a mausoleum for the internment of family members.

In Buenos Aires, Argentina, mausoleums are bought and sold like real estate.

Back in the day, it was not unusual in many places throughout the world to have photographs taken with a deceased relative.

But that was when photography was something to be experimented with. Post Mortems was one of the most photographed rituals back in the day.

Down through time, we have become more squeamish about death. We get others to look after our elderly (nursing homes, retirement homes etc.

The Torajans would be extremely disappointed at such a proposal.

Even though many Torajans have all the modern devices, attend modern schools and universities, they still hang on to the belief of eternal life.

Credits and Further photos and information:

Thanks for reading. As always, feel free to leave any comments below.

Free E-Book.

Grief is an intricate emotion, often likened to a journey through a maze with its unique twists, turns, and challenges. Though everyone’s experience with grief is personal, there are shared elements that many encounter.

By understanding these aspects and equipping oneself with coping mechanisms and supportive environments, it’s possible to find meaning, healing, and even growth in the face of loss.

So true Ryan,

I remember going into the underground corridors of a church in Lima (Peru), where they had the bodies of about 5,000 kids and adults stacked up in open coffins, who had died from some plague 3 or 400 years ago, and listening to the fearful voices of the women in the group.

The one I remember most was the loud, distinctive middle eastern wailing of an Egyptian woman.

She exited back to the entrance, and was visibly upset and shaken by the ordeal.

Thank you for the response, it is greatly appreciated.

Fascinating post Michael. Westerners are often so scared of even mentioning the word death, and often to terrified to discuss the concept.

This is literally insane because we all lay the body aside; we may as well discuss it, lighten up and learn from more spiritually advanced cultures how to meet and greet the usefulness of the body coming to an end.

Ryan